A second iron age

CDG

48˚ 51’ 32” N | 2˚ 17’ 40” E

CDGE07015*

Paris’ iconic monument is painted three shades of ‘Eiffel Tower Brown’ to give it a uniform appearance when seen through atmospheric haze. © Vast Compass, 2025.

Knowledge lost to time

By the time of 1889’s Exposition Universelle, engineering entrepreneur Gustave Eiffel headed a highly successful eponymous business with increasingly global reach. His engineering know-how and depth of experience made wrought iron ascendant in an age during which architects and builders were pivoting away from wood and stone, but when concrete was not yet re-perfected.

Knowledge to successfully achieve Rome’s facility with concrete 2,000 years earlier is one of the most interesting chapters of the Dark Ages when so much wisdom that came before was lost to time. Even now researchers study Rome’s Pantheon to understand the building’s ancient secrets hidden inside its mathematical marvel of a concrete sphere inside a concrete cube.

The Pantheon is a building I never tire of visiting. Atmospherics inside the great dome shift every few minutes as light streaming through the oculus reminds us the building is more than a monument, it’s also a celestial timepiece. Each moment across the day and year is unique, the changing angles of light and shadows vivid reminders of the passing of time, like sand falling from an hourglass as wide as the sky itself.

FCOE13027*—A 142-foot sphere as wide as it is high would fill the Pantheon exactly. And at 5,000 tons, the unreinforced concrete dome still holds the record for its type of construction. On its perimeter the dome is 21 feet thick.

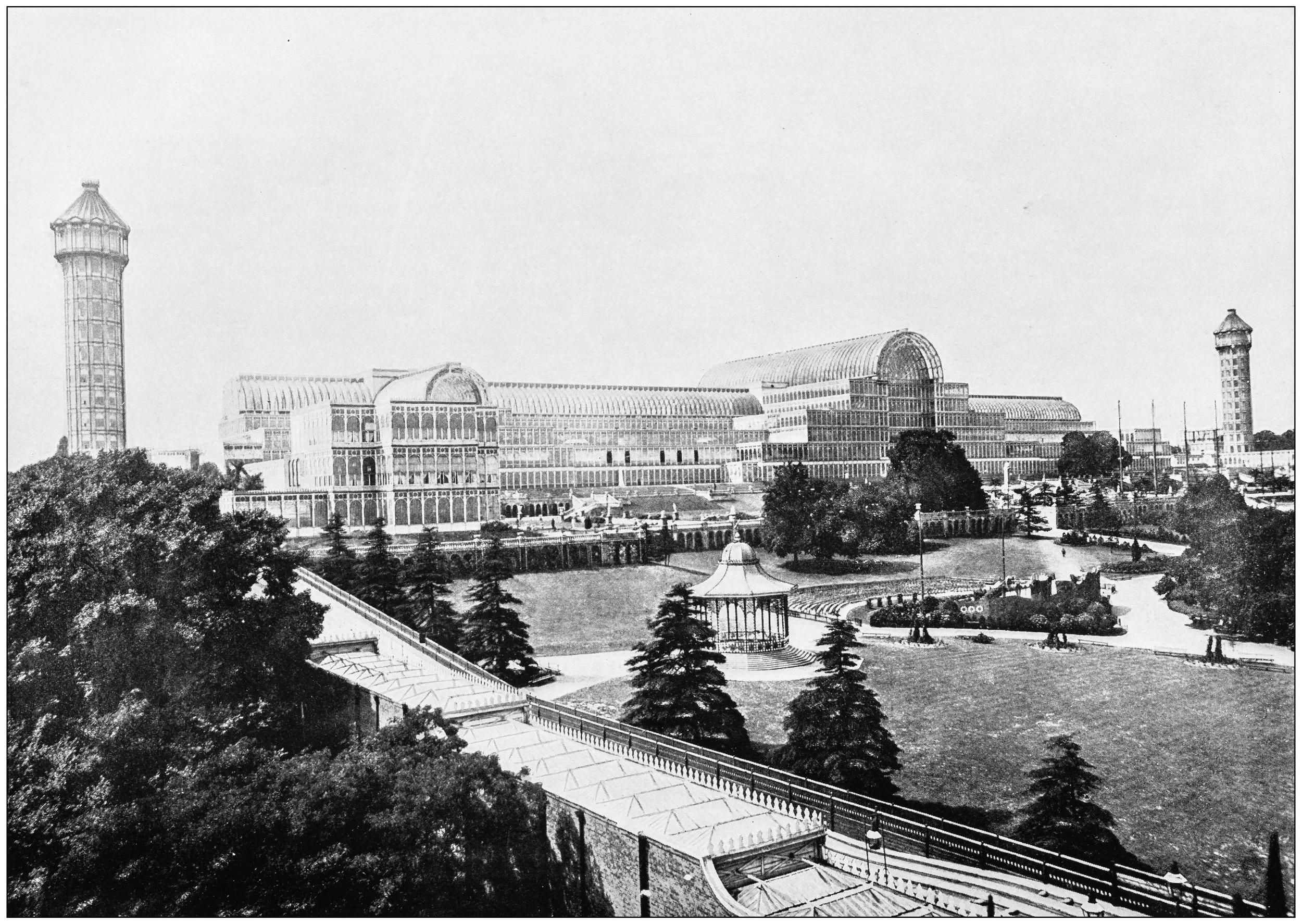

Iron here, there, everywhere

London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 gave us the Crystal Palace, a revolutionary building made of pre-fabricated iron parts and featuring the largest expanse of glass to that time. Built of cast iron and plate glass, the 900,000 square foot superstructure was three times the size of St. Paul’s Cathedral and showcased displays of the latest innovations powering the Industrial Revolution. Iron and glass parts, fabricated elsewhere, were quickly assembled onsite. After the Exhibition closed, the Crystal Palace was moved to a different part of London. It was most lost to fire in 1936, with its remaining few towers destroyed during the Blitz.

The Crystal Palace

Visitors to the Great Exhibition of 1851 were astonished at the experience of being inside a structure which required no interior illumination during the day. Iron and glass parts, fabricated elsewhere, were quickly assembled onsite. After the Exhibition closed the Crystal Palace was moved to a different part of London. It was mostly lost to fire in 1936, with its remaining few towers destroyed during the Blitz a few years later.

Photo credit: Lbusca, iStock.

Re-defining construction

The Crystal Palace joins other innovative uses of iron re-defining construction at the time—it was a second iron age, if you will. Across the Pond, in America John Roebling was reimagining the business of bridge construction with iron rope suspension designs—his now-iconic Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883. And Gustave Eiffel was busy transforming cityscapes with numerous iron projects coming from his studio, Compagnie des Établissements Eiffel. They include Budapest’s Nyugati Railway Station (1875), the Maria Pia Railway Bridge in Oporto, Portugal (1877), the Garabit Viaduct in France (1884), and a dome for the Nice Observatory (1886).

NYCE08010*—The Brooklyn Bridge, shown with one of four installations by artist Olafur Eliasson. The New York City Waterfalls were in place from June 26, 2008 to October 13, 2008.

Budapest’s Nyugati Railway Station by Gustave Eiffel. Photo credit: Herbert Ortner, Wikimedia Commons.

NYCE08011*—Completed in 1869, John Roebling’s Brooklyn Bridge used 14,000 miles of steel wire in its cables. Weighing 3,500 tons apiece they were the longest and heaviest cables that had ever been made.

Gustave Eiffel’s Ponte de Dona Maria Pia in Oporto, Portugal. Photo credit: joyt, iStock.

In Oporto we bought a ceramic trivet on which the Maria Pia bridge by Eiffel makes a stylized appearance.

SFOE16001*—More than 80,000 miles of steel wire are used in the Golden Gate Bridge’s cables. Their aggregate weight is 24,500 tons. In 1937 it took 6 months and 9 days to spin the cables from wire.

SFOE16011*—The Golden Gate Bridge uses 1.2 million rivets. A commemorative replica rivet finished in iconic Internal Orange paint is available in the bridge gift shop and online for $7.95. (An Eiffel Tower rivet retails @ $600.)

SFOE16021*—1,600 feet in length, the Brooklyn Bridge took 14 years to build. The Golden Gate Bridge, with a length of 4,200 feet was completed in just a bit more than three years. The numbers reflect an acceleration of innovations in the 20th century made possible by forebears like Eiffel and Roebling in the late 19th century.

INTERNATIONAL ORANGE

Two shades of so-called International Orange are used in maritime and engineering applications globally. A third is used on the Golden Gate Bridge and often ‘borrowed’ by other bridges around the world. All three colors are like safety orange (think traffic cones) in that the color sets objects apart from their surroundings in a wide spectrum of lighting conditions, but all three are deeper hues,

with more red used in their formulation.

Popular with publishers on books about the Golden Gate Bridge, International Orange is also used to powder coat commemorative rivets and bookends, both sold in the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy shop.

SFOE16031*—The dramatic color looks great against azure skies, even as it’s real purpose—to be visible in low light and foggy conditions—is all about safety. The color has a CMYK formula of 0% Cyan, 69% Magenta, 100% Yellow, and 6% Black.

Variants of International Orange are used in aerospace for test aircraft and flights suits. It also makes an appearance on Tokyo Tower to comply with international aviation regulations. Readers of this blog will recognize the Tokyo Tower from another post, where I ask, “Is imitation really the most sincere form of flattery?” Photo credit: yongyuan, iStock.

LISE11079*—If Lisbon’s Ponte 25 de Abril (25th of April Bridge) looks familiar, there are reasons. One, it was built by the same company as the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge (the firm was chosen given their experience building in earthquake-prone zones). Two, it’s painted the same International Orange as the Golden Gate Bridge.

The artist vs. the engineer

Understatement doesn’t begin to capture the irony that the architect for the observatory in the south of France was Charles Garnier, soon to be one of the Eiffel Tower’s harshest and most well-known critics. Today we might call Eiffel and Garnier as ‘frenemies’. Or, as professionals engaging in ‘coopetition’. That is, competitors cooperating as they worked on a common project. Tensions of the day are made clear when considering Garnier’s eponymous opera house alongside the Eiffel’s eponymous Tower. Garnier described his opulent Palais Garnier as having been conceived and built in the Napoleon III style, an eclectic mash-up of references across the ages from the classicism of Palladio to the High Renaissance and Baroque. Iron was used in its construction in 1875, but it remains largely hidden behind traditional wood and stone.

It's a gorgeous building, and to our eyes—with distance and time—both Garnier’s opera house and Eiffel’s monument are equally ‘French’. They appear as equals on the tourist’s itinerary.

Still, considered in the context of the era in which they were brought to life, the two structures couldn’t be more different. The clash centered on a debate between art and engineering, laid bare. If I may paraphrase those in Garnier’s camp:

One structure celebrates and enshrines architectural glories from the past to beautiful effect in the present, the time-honored

craft of artisans from sculptors and carvers to muralists and marqueters dazzling the eye at every turn. The other structure is

simply a naked framework conceived with no artistic forethought and roughly executed with merciless efficiency its only aim,

the whole thing a mere result of cold mathematics and brute assembly on a factory floor.

CDGE13401*—Palais Garnier encapsulates numerous styles from traditional European architecture across the centuries to beautiful effect. It’s as iconic in its way as Notre Dame de Paris, the Sydney Opera House, and...the Eiffel Tower.

CDGE10046*—The opera house’s grand gallery is gilt and muraled and glowing with crystal chandeliers above marquetry floors spanning the full width of the building behind the colonnade on its second floor, seen left.

CDGE13311*—The Eiffel Tower wears modernity with pride, its manufactured elements as plain as its mechanical assembly. Rivets and trusses only add to its visual interest. The Tower’s lattices and filigree, its decorative corbels, and its warm hue conspire to defuse the shock of the new by way of references to the past. Old and new are simply part of a greater gestalt. She’s the punk girlfriend in a leather biker jacket and lace-fringed camisole.

CDGE13408*—Fans of the stage musical and movie Phantom of the Opera thrill to the scene in which Christine and Raoul sing All I Ask of You among statuary and on the opera house’s rooftop. Surreptitiously listening, the masked Phantom hears them declare their love for one another in song. In a jealous rage the vengeful Phantom sabotages the auditorium’s massive crystal chandelier in order to bring it crashing down.

Given Charles Garnier’s impassioned protest against Eiffel’s modern Tower 77 years prior, it’s impossible not to wonder what the hide-bound aesthete would have felt about Marc Chagall’s oh-so-20th-century mural installed above his namesake opera auditorium in 1964.

But first, Liberty

Until the 1889 exposition, the renown of Gustave Eiffel’s studio didn’t come from a public hue and cry against his Tower. Instead it came most widely from its having created the iron framework inside Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s Liberty Enlightening the World, better known as the Statue of Liberty, rising at the entrance of New York City’s harbor.

Two years and eight months

The commission to provide the Statue of Liberty’s armature was originally awarded to Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, best known to most of us for his addition of the iconic spire atop the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral. Viollet-le-Duc proposed supporting Lady Liberty with brick piers filled with sand.

Viollet-le-Duc’s most well-known project

By the time the famed French architect was contracted to construct the internal framework for the Statue of Liberty, Viollet-le-Duc had spent decades putting his signature on projects across France, notably Château de Pierrefonds, Mont Saint-Michel, Sainte-Chapelle, and Notre-Dame de Paris. Many of his contemporaries and critics ever since have been vocal in their opposition to much of le-Duc’s work, insisting his ‘restorations’ imposed a Gothic sensibility on buildings, rather than adhering to historical accuracy.

Still, it’s thanks to le-Duc that Notre Dame’s iconic sculptural façade was repaired following devastation enacted during France’s bloody Revolution. He also restored the building’s iconic gargoyles and grotesqueries which had been removed during the reign of Louis XIV. And he inaugurated a new spire atop the cathedral in 1859.

160 years later the world held its collective breath while watching a live stream as the cathedral’s beloved spire fell to raging flames fed by oaken timbers more than 1,000 years old.

CDGE13226*—From 1859-60 Viollet-le-Duc worked to replace the spire above the crossing of the transept and nave of Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris. When it was lost to fire in 2019, the world mourned, but swift action resurrected the spire by 2024, using Medieval wood-building traditions fused with 21st-century technologies like LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and Building Information Modeling (BIM).

CDGE07051*—In vivid verdigris, statues of the 12 Apostles and 4 Evangelists were a seminal part of le-Duc’s spire design. Amazingly, all 16 statues were removed for restoration mere days before the 2019 inferno, ensuring they were not lost to the cathedral’s devastating flames.

Viollet-le-Duc’s armature for Notre-Dame’s spire was made of 1,000-year old oak. Ancient trees were similarly felled to create the new spire unveiled in 2024. Photo credit: LEVRIER Guillaume, Wikipedia.

Notre-Dame Cathedral’s 19th-century spire took the place of one lost to decay the previous century. Here le-Duc’s replacement burns while the world looks on in horror across hours on April 15, 2019. While iron was used in some aspects of Notre-Dame’s construction, the armature for the spire was made of ancient oak, a spidery web-y network of cracked and tinder-dry fuel primed for lethal ignition . David Henry, iStock.

Viollet-le-Duc’s original drawing for Notre-Dame’s replacement spire in the 19th century extended the height of the original 13th-century spire by 60 feet, topping out 315 feet above the cathedral floor. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Notre-Dame’s bell towers are 226 high. Its ‘flèche’ (arrow) brings the building to a total height of 315 feet. Viollet-le-Duc’s spire design required 500 tons of wood covered in 250 tons of lead. The new spire was revealed on February 13, 2024. Photo credit: Jean-Luc Ichard, iStock.

For five years, an intricate universe of scaffolding surrounded Notre Dame de Paris as workers from structural building trades (carpenters, roofers, stone cutters, stained-glass glaziers, metal workers, cabinet makers, and joiners) joined those from works management trades (engineers, project managers, and draftspeople) to ply their crafts in restoring the iconic cathedral. Photo credit: yann vernerie, iStock.

The timbered attic of Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris is called La Forêt—the forest. By 2027 a new literal forest will frame the restored church. The landscape re-development is adding 131 new trees and increasing garden space near the monument by 30%. Re-connecting the cathedral grounds with embankments along the Seine will transform disparate parts of the property into a unified park from its western approach, along its south, and wrapping to the east and north. Shaded benches will provide new views of the church, and a new ‘fountain’ will wash over its plaza periodically in summer, both cooling the air and providing a fleeting reflective mirror of flooded stone. Detractors detect a whiff of English garden design that is at odds with French sensibility which historically favors a more controlled and manicured landscape. Image credit: Bas Smets

Passing the baton, twice

Viollet-le-Duc died in 1879, which is how the project of building the Statue of Liberty’s internal support was passed to Eiffel to complete. By then Eiffel’s knowledge of wind shear and the physics of working with wrought iron were more advanced than any other engineer in the world. Across 32 months from 1881-1884, his studio forged and welded a massive four-legged pylon and truss system to provide a flexible skeleton for the colossus. The framework’s 1,300 puddled iron bars, if placed end to end, would stretch more than a mile. Each weighed about 20 pounds.

With the Statue of Liberty’s iron armature complete it was time to pass the baton once more, from Eiffel’s studio to the craftsmen at Gaget, Gauthier et Compagnie workshop who proceeded to hammer the statue’s 300 copper panels into bespoke forms to create Lady Liberty’s robes, hands, and diadem using the repoussé technique—a process created by Viollet-le-Duc.

Next, From Port Said, to Say what?

Recommendations

Monuments across history have origin stories as compelling as their places in our lives. These books capture the backstory of civic architecture on two coasts of America, relaying in vivid detail the men and women responsible for the icons we see today. Symbols of a nation’s spirit of innovation and the cities whose personas they exemplify.

The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge

From Amazon

“A monumental tale of American ambition, told by Pulitzer Prize–winning author and master historian David McCullough. This gripping saga of the creation of the Brooklyn Bridge, one of the country’s boldest engineering achievements, reveals not only the politics and personalities behind ‘America’s Eiffel Tower,’ but charts New York’s ascent as a thriving metropolis.”

Golden Gate Bridge: History and Design of an Icon

From Amazon

“Nine million people visit the Golden Gate Bridge each year, yet how many know why it's painted that stunning shade of "international orange"? Or that ancient Mayan and Art Deco buildings influenced the design? Current bridge architect Donald MacDonald answers these questions and others in a friendly, informative look at the bridge's engineering and seventy-year history.”

Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America's Greatest Bridge

From Amazon

“Kevin Starr's Golden Gate is a brilliant and passionate telling of the history of the bridge, and the rich and peculiar history of the California experience. The Golden Gate is a grand public work, a symbol and a very real bridge, a magnet for both postcard photographs and suicides. In this compact but comprehensive narrative, Starr unfolds the hidden-in-plain-sight meaning of the Golden Gate, putting it in its place among classic works of art.”