Enshrined in our collective consciousness

CDG

48˚ 51’ 32” N | 2˚ 17’ 40” E

Built for the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie ModerneIt in 1937, the Fontaine de Varsovie (Warsaw Fountain) has 12 fountains that create 50-foot-high columns of water, 24 smaller fountains reaching 12 feet , and 10 water arches. In total they propel more than 1,500 gallons of water per second. © Vast Compass, 2025.

‘Hateful’ pre-fab, vs. hand-carved

Built for the 1889 Exposition Universelle, the Eiffel Tower served as a gateway to the world’s fair being held in Paris to mark the centennial of the French Revolution, and to celebrate the nation’s ideals of liberté, égalité, and fraternité represented in its blue, white, and red flag. The exposition’s official name was the Exposition Tricolorée.

Get a ‘clou’

During an open competition, architects and engineers (not to mention a few crackpots) put forward some 700 designs to build a structure around which the exposition would be organized—that is, a 300-meter ‘clou’, or spike, that would physically anchor the fair. 90% were rejected outright.

Including one submission of a 1,000-foot guillotine meant to symbolize the French Revolution a century earlier and simultaneously honor the 17,000 French citizens lost to the Reign of Terror from 1793-1794 (To be fair, the Fair was timed to commemorate the downfall of France’s monarchy and subsequent birth of the French Republic). Another entry proposed a large ‘watering can’ design that could sprinkle fair goers below with cool water on hot afternoons. So, there were options galore.

A memorial to Revolution

Oui, a 1,000-foot high guillotine monument was proposed to serve as gateway to the 1889 Exposition Universelle. Fortunately, macabre and fanciful entries from the fringe were winnowed from official competition with final selection being from just nine submissions falling more in the mainstream. Still, the instrument of public execution wasn’t necessarily seen as being in bad taste at the time, so much as an acknowledgment of fact. When A Tale of Two Cities was serialized in 31 installments in the periodical, All the Year Round, Charles Dickens’ long-time collaborator ‘Phiz’ featured a guillotine on the cover of a July 1859 issue. Photo credit: PD-1923/BnF.

Tradition vs. the avant-garde

But what civic boosters and politicians wanted was a 1,000-foot tower, and Gustave Eiffel had the studio and experience to deliver it. He even had ways to put his thumb on the scale as a member of the committee charged with awarding the commission. But, oh so much stood in his way.

First, there were his competitors. While many of the 68 designs under serious consideration were from the mainstream, others were best described as mainstream-adjacent, given that they blatantly represented modernity and not a classical French style—alas, Gustave Eiffel’s design was in this category.

Lively debate between various schools of thought commenced: Between tradition and the avant-garde, between stone and iron, and especially between Beaux-Arts refinement and Belle Époque elegance, and the stark nakedness of structural mechanics made possible only by pre-fab manufacturing. We know pre-fab won the day but, Mon Dieu!, feathers were ruffled.

High dudgeon in black and white

On February 14, 1887, a committee of 300 renowned artists and aesthetes published an open letter in Le Temps decrying the tower. Each single member symbolized a single meter of the monument’s proposed 1,000-foot height.

“We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection...of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower.”

The tower’s naked modernity of machined iron and exposed rivets—so clearly a design conceived by engineers—offended a coterie of artists who scorned it as a “hateful column of bolted sheet metal”, with no semblance to classically beautiful architecture built of stone. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Will the city of Paris continue to associate itself

with the baroque and mercantile fancies of a builder of machines,

making itself irreparably ugly and bringing dishonor to itself?

—Among the 300 signatories to the published “Protest against the Tower of Monsieur Eiffel”: painter Ernest Meissonier (first president

of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts), Charles Garnier (architect of the Paris Opera), and Charles Gounod (composer)

Protest with a view

The petition, titled Artists against the Eiffel Tower, was a declaration of aesthetic judgment against the monument. Guy de Maupassant called the Tower, “a giant ungainly skeleton...a lanky pyramid...a ridiculous, skinny, factory chimney stack”. He’s is said to have frequently dined at one the Eiffel Tower’s restaurants—not for its cuisine, but because it was, “the only place in the city where I won’t see it”. It’s a criticism lobbed by Parisians at 20th-century buildings Tour Montparnasse and La Défense. Photo credit: clu, iStock.

In the same edition of Le Temps, Gustave Eiffel defended his eponymous tower in vigorous language.

What are the reasons given by the artists for protesting

against the maintenance of the tower? How useless, how monstrous!

What a horror! We’ll talk about usefulness later. Let us concern ourselves,

for the moment, only with the aesthetic merit, on which the artists are more particularly competent. I would like to know on what they base their

judgment. Because, mark it, sir, my tower, nobody saw it and nobody,

before it was built, could say what it will be.

The Times, France’s paper of record

Clearly, Eiffel’s feathers were ruffled too. Of course, he was just the latest in a long list of visionary architects castigated by ‘nattering nabobs of negativity’ granted access to a bully pulpit like Le Temps with a daily circulation of 950,000, the highest of any newspaper in the world in 1887.

She doesn’t stand alone

The Eiffel Tower is in good company, with every age having its naysayers as late-breaking developments in design and materials threatened to sweep away the past. As just a handful of comments triggered by now-iconic architecture show below, over-wrought opinions freely shared by critics are a predictable trope.

SEAE01001*—When reviewing Frank Gehry’s Experience Music Project (EMP) building (now the Museum of Pop Culture [MoPOP]), Herbert Muschamp, architecture critic for The New York Times, described the complex in Seatle, Washington as, "something that crawled out of the sea, rolled over, and died".

SYDE13041*—Davis Hughes, the Minister for Public Works in New South Wales during a crucial period of building the Sydney Opera House said of architect Jorn Utzon, “He was a sculptor. He was not an architect.” Others called Utzon’s astonishing building, “a heap of broken meringue shells", “a pastry gone wrong”, and, “a prawn on its back.”

CDGE13391*—Hector Guimard design 167 art nouveau entrances to Paris’ metro system. Critics called the verdigris-inspired color as, “German”. The bespoke lettering was deemed “un-French”, and, from Andre Hallays in Le Temps, “confus[ing to] little children who are trying to learn their letters.” While only 86 of Guimard’s entrances remain, they are now protected.

CDGE12163*—When the Pompidou Center (Centre national d'art et de culture Georges-Pompidou) was reviewed by National Geographic in 1977, the magazine declared it was, “love at second sight,” because of the building’s ‘inside-out’ design with various systems housed in color-coded pipes and ducts. Le Figaro was even more to the point, writing, "Paris has its own monster, just like the one in Loch Ness."

The grande dame

Of course, we know how the story ends. Eiffel’s achievement rises, riveted part by riveted part, and takes its place in the canon of architectural superstars. And Parisians, including several of the artists who derided the project as folly, eventually came around. The Iron Lady today is the grande dame of the Paris skyline and remains the very symbol of France itself.

Recommended

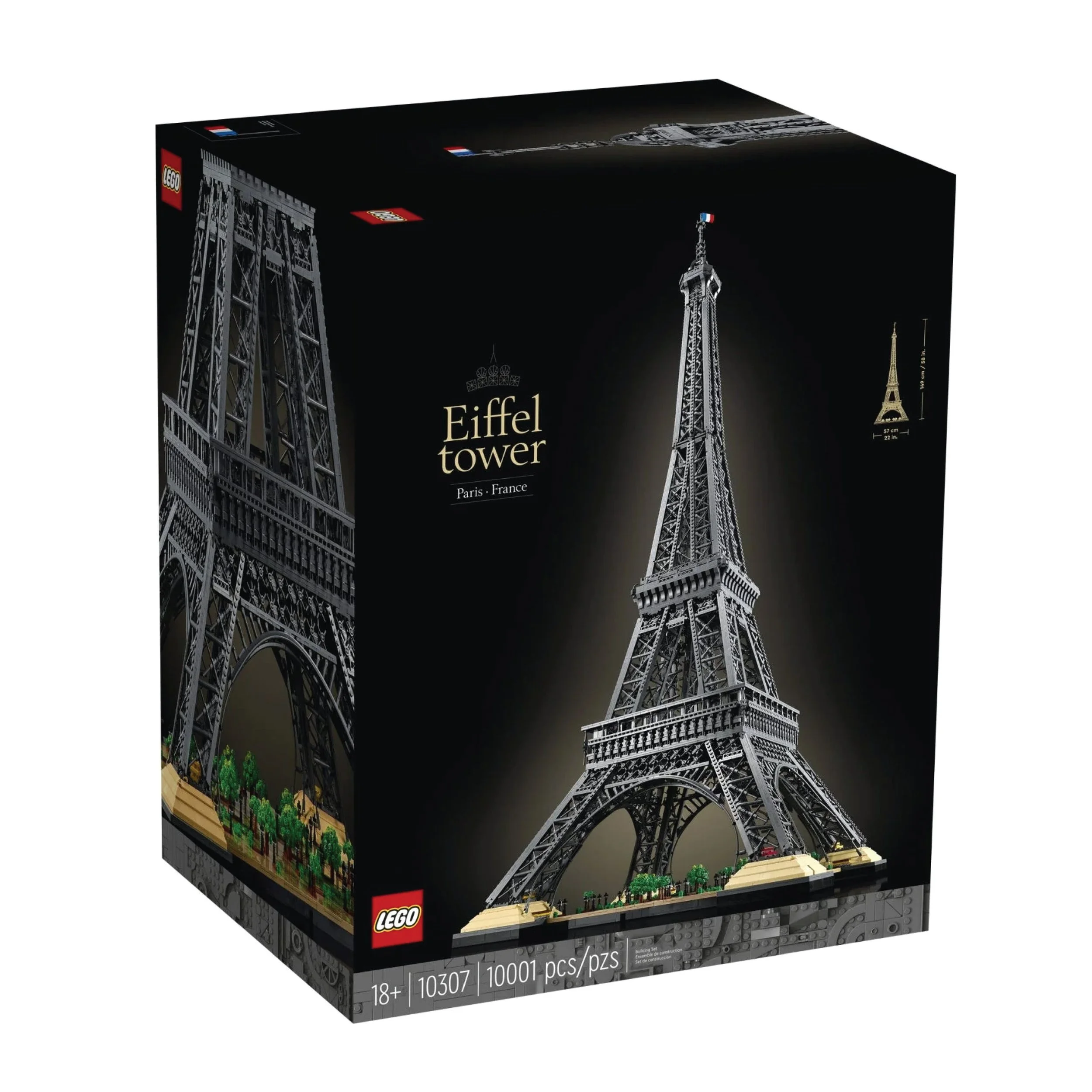

The Eiffel Tower set from LEGO is designed from 10,001 pieces (shy of the Tower’s 18,038 pieces IRL). Nearly all LEGO bricks are made from Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) plastic—strong, durable, and scratch-resistant with a unique ‘clutch power’ for connecting tightly. LEGO also uses polycarbonate for transparent elements and polyethylene for soft, rubbery parts. Fully assembled, the LEGO Eiffel Tower measures 58” high.

LEGO Eiffel Tower Set 10307

From Amazon

“A build like no other. Get ready to break records with this LEGO Eiffel Tower model set for adults. With a height of almost 1.5 metres and 10,001 pieces, it is a collector's item that you will love forever. Faithful geometry. This 360 model follows exactly the decoration of the real Eiffel Tower with arches, supports, cross braces, railings and even a faithful view when you look from bottom to top.”